The Edge AI: the new development paradigm.

In recent years, thanks in part to major social and technological changes across continents, we are experiencing an acceleration in the development of artificial intelligence, so-called AI.

Thanks to advances in algorithms and computing power applied to big data, deep learning-the most brilliant area of AI-has made great progress in many fields, ranging from computer vision, speech recognition and natural language processing to robotics.

It is widely recognized that intelligent applications are significantly enriching people’s lifestyles, seeking to improve human productivity and social efficiency.

As a key factor in the development of artificial intelligence, big data has recently undergone a radical transformation of the source of data processing, moving from cloud-based data centers to increasingly popular end devices, such as, for example, mobile devices and Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices including industrial-grade (IIOT).

Traditionally, big data was born and stored primarily in large hyperscales, datacenters of very large capacity distributed on a global scale. However, with the proliferation of mobile computing and IoT, the trend is changing: in fact, the huge volumes of data that need to be moved from terminal devices to the cloud for centralized processing create a significant increase in the cost of managing link infrastructure and processing time.

Pushing toward the edge ecosystem, however, is not a trivial task.

The trend, in fact, was to transport the masses of data from local devices to cloud data centers for analysis. However, when moving huge amounts of data across the network, both the cost and the transmission delay can be prohibitive as well as the loss of privacy.

In recent years, the concept of “on-device” computational analysis, which runs artificial intelligence applications on the device (the “edge” precisely) to process IoT data locally, has been introduced. Such devices, however, can suffer from poor performance and energy efficiency. This is because many AI applications require high computing power that far exceeds the capacity of IoT devices, which are resource and energy limited.

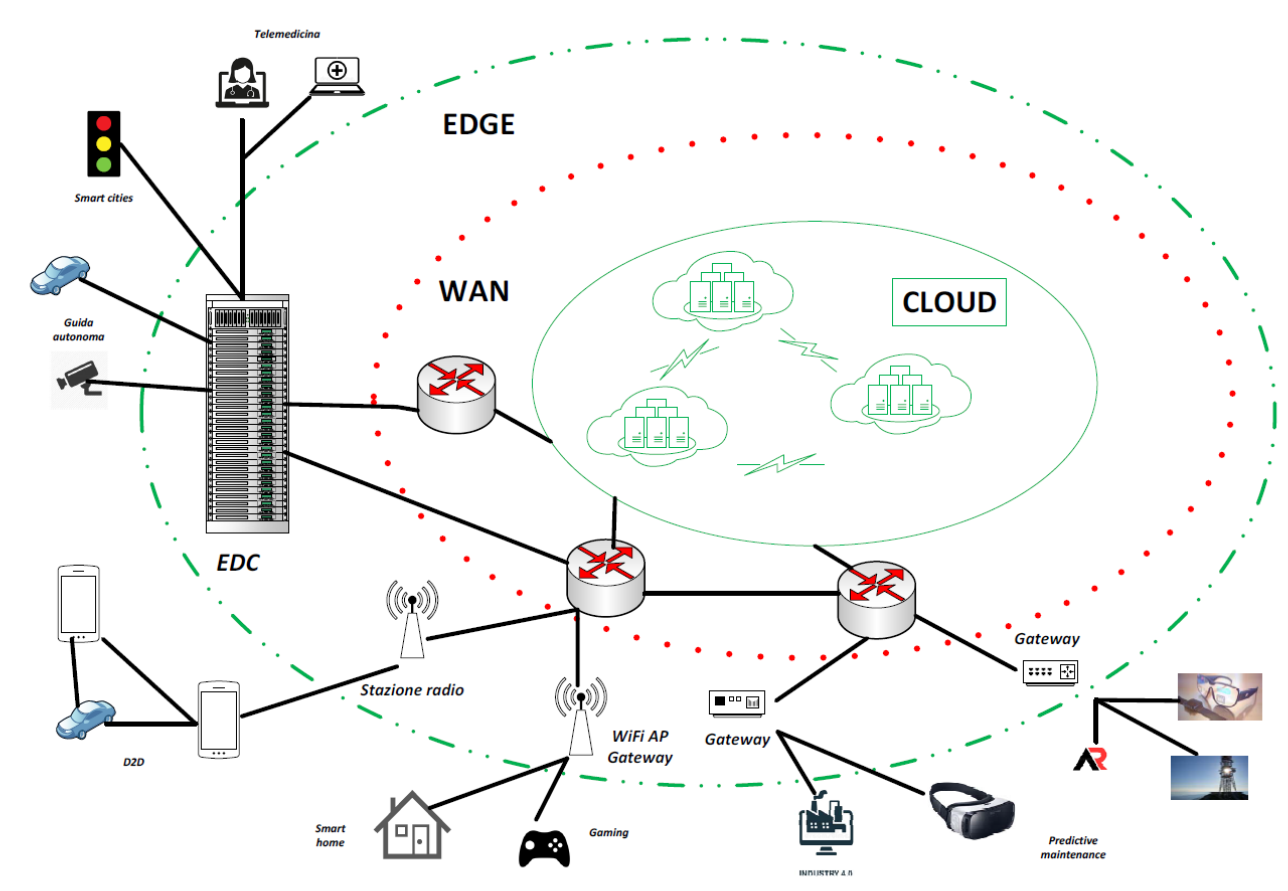

To realize the above project, the technology community a introduced edge-computing, which pushes computational services from the network core (cloud) to the network edge (edge), closer to local devices and data sources.

An edge node can thus be a local end device that can be connected via device-to-device (D2D) communications, a server connected to an access point (e.g., a WiFi Access Point, a radio base station), a network gateway, or local micro datacenters (called “edge datacenters”) available for use by neighboring devices. Edge nodes can thus range in size from a computer the size of a credit card to an edge datacenter with numerous racks of servers.

Physical proximity to information generation sources is thus the most important feature emphasized by edge-computing. In essence, physical proximity between processing and information generation sources enables advantages over the traditional cloud-based processing paradigm, such as low latency, energy efficiency, privacy protection, and reduced bandwidth consumption.An edge node can thus be a local end device that can be connected via device-to-device (D2D) communications, a server connected to an access point (e.g., a WiFi Access Point, a radio base station), a network gateway, or local micro datacenters (called “edge datacenters”) available for use by neighboring devices. Edge nodes can thus range in size from a computer the size of a credit card to an edge datacenter with numerous racks of servers.

The marriage of edge computing and AI has given rise to a new area, “edge intelligence (EI)” or “edge AI.” Instead of relying completely on the cloud, EI leverages widespread edge resources to achieve the desired computing power.

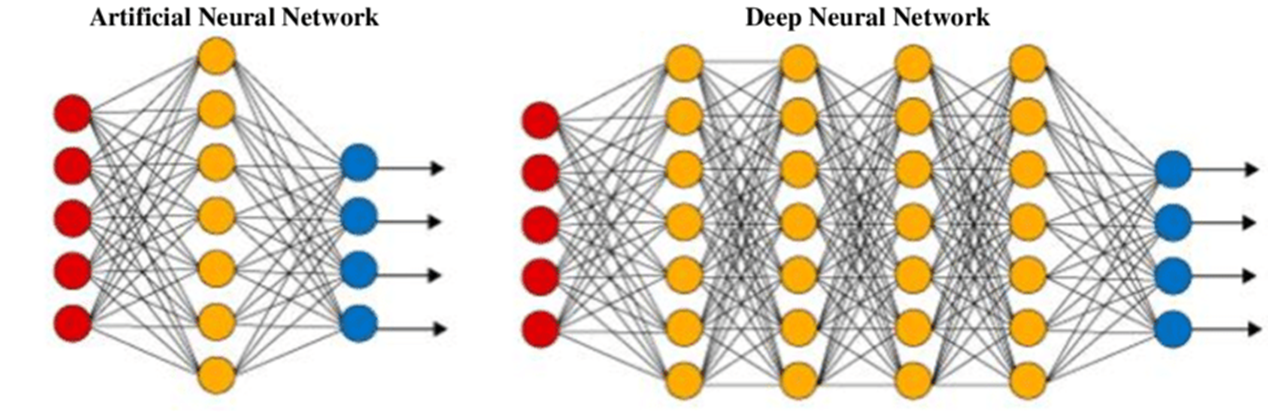

Although AI has recently risen to prominence, it is not a new term and was first coined in 1956: it is an approach to building intelligent machines that can perform human-like tasks. One branch of AI is machine learning (or “machine learning”-shortened ML).

Many ML methodologies, for example, decision trees, K-Means clustering, SVMs (Support Vector Machines) and neural networks, have been developed to train the machine to produce classifications and predictions, based on data obtained from the real world.

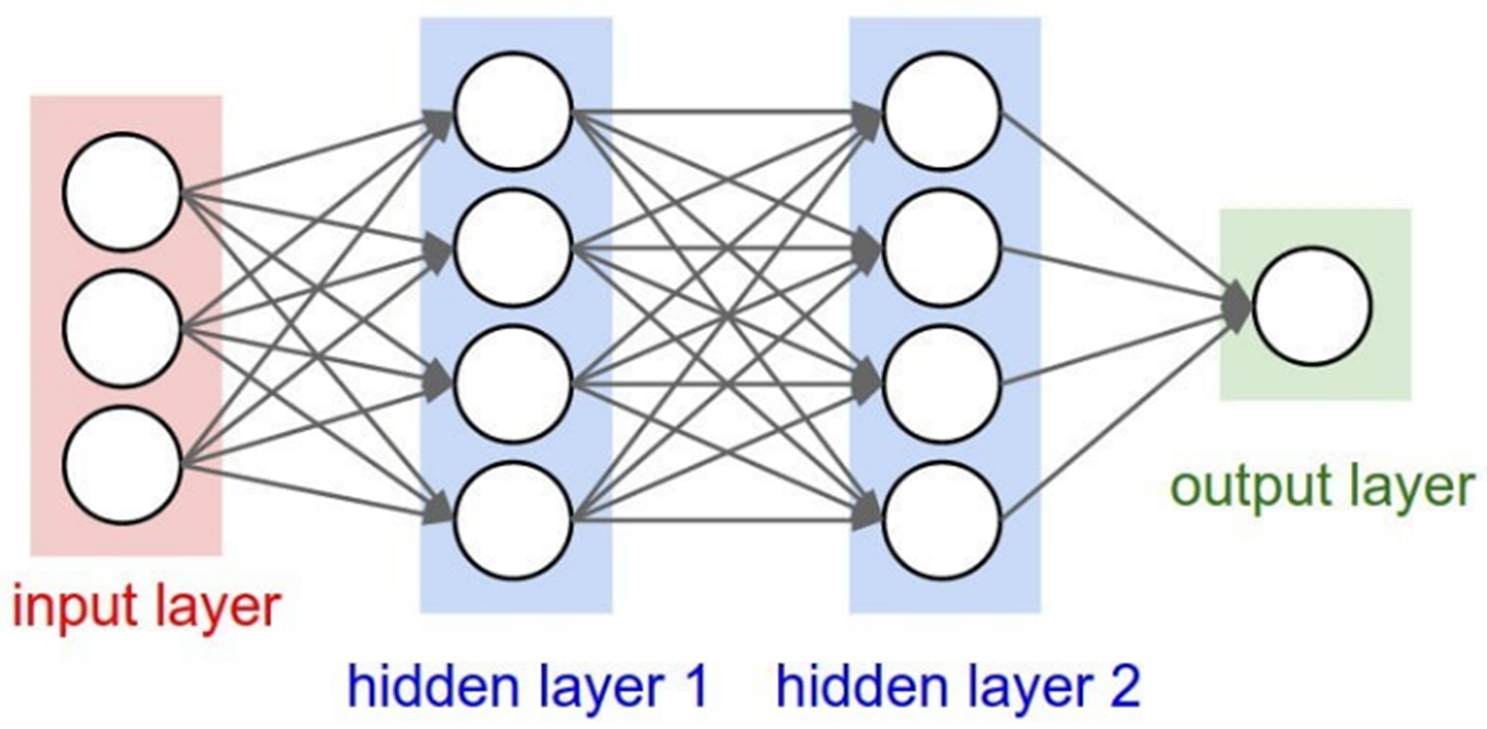

Among the most computationally demanding ML algorithms we have deep learning, which, relying on “deep” neural networks, has led to very important performance in several fields, including image classification, face recognition, audio signal classification, and so on. Since deep neural networks typically consist of a series of layers, the model is called a deep neural network (DNN) in which each layer of a DNN is composed of neurons that are able to generate nonlinear outputs based on data from the neuron input.

By feeding a large number of training samples and repeating this process until the error rate is below a predefined threshold, a learning model with high accuracy is obtained.

Inference (i.e., prediction based on new data) of the model occurs after training. For example, for image classification, by feeding a large number of training samples, a DNN is trained to learn to recognize an image; then, inference takes real-world images as input and quickly derives predictions/classifications from them.

Edge-computing has lately become critical for applications that leverage the above algorithms for real-time inference, as edge-computing aims to coordinate a multitude of collaborative edge devices and servers to process data generated in close proximity.

As a result of the proliferation of the number and types of mobile and IoT devices, large volumes of multimodal data (e.g., audio, image, and video) from the environment are continuously being collected from the device side. In this context, Edge-AI is indispensable because of its ability to rapidly analyze these huge volumes of data and extract useful information from them to make high-quality decisions.

In fact, deep learning offers the ability to automatically identify patterns and detect anomalies in data sensed at the edge, such as traffic flow in smart cities, telemedicine, environmental, electrical and audio data to capture anomalies in machine operation, and autonomous driving.

The predictions extracted from the model built on the sensed data are then used for real-time predictive decision making in response to rapidly changing environments, increasing operational efficiency.

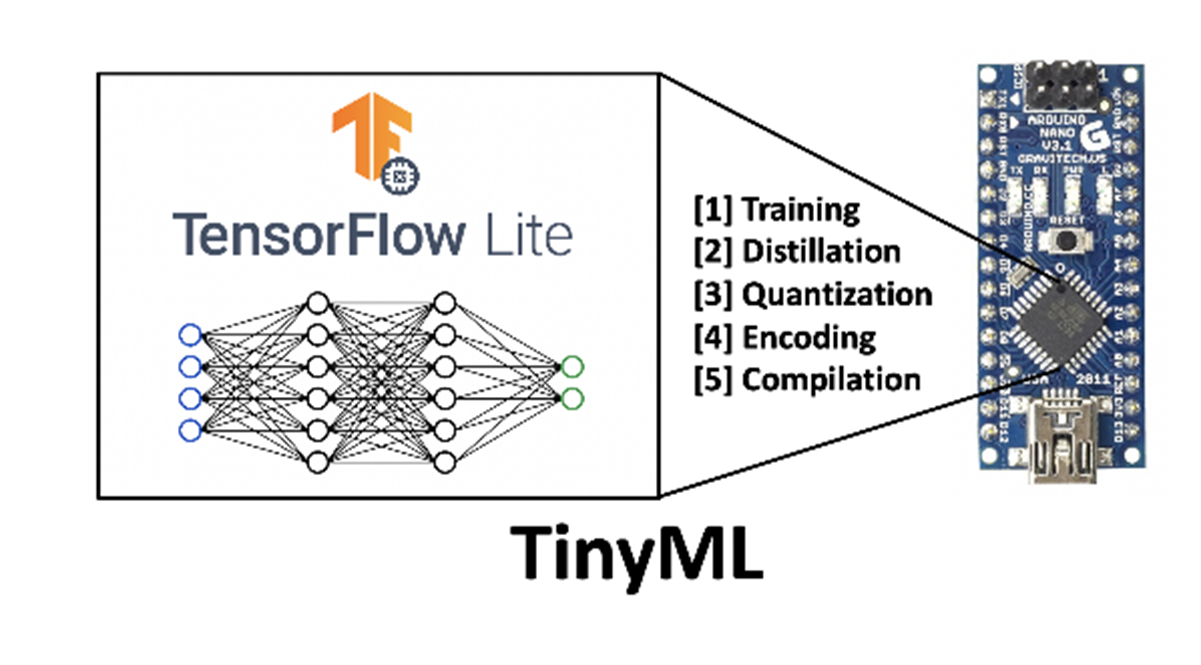

As a further enhancement in the past couple of years, the paradigm of running AI algorithms locally on an end device with data (sensor data or signals) processed on the device, so-called “TinyML,” is gaining momentum, although such processing is limited by the performance of the microprocessors used on the end devices.

Here then is where Edge-Ai can be well represented with the computational marriage between edge data centers and end devices, depending on the performance to be achieved. It is what enables the “democratization of AI” today, that is, the vision of “making AI usable for every person and every organization, everywhere.”

The scope of EI, however, should not be limited to running AI models exclusively on the server or edge device. In fact, as studies on the subject have shown, for DNN models, execution with edge-cloud synergy can reduce both end-to-end latency and energy consumption compared to the local execution approach.

IE should be the paradigm that fully exploits the data and resources available in the end-device, edge node, and cloud data center hierarchy to optimize the overall training and inference performance of a DNN model. However, this does not necessarily mean that the DNN model is fully trained or inferred at the edge, but that it can perform in a coordinated cloud-edge-device manner through data offloading. Specifically, based on the amount and length of the data offloading path, we classify EI into six levels, as shown in Fig.

Specifically, seven levels [1] can be defined constituting a continuum between the cloud computing of hyperscales, edge datacenters and end devices.

1.Level 0: training and inference completely in the cloud

2.Level 1: training in the cloud, but inference cooperatively edge-cloud; in this case, edge-cloud cooperation implies partial offloading of data to the cloud

3.Level 2: training in the cloud, but inference is performed “in-edge,” which can be accomplished by fully or partially offloading data to edge servers or nearby devices

4.Level 3: training in the cloud and inference on the end device “on-device”: in this case no data is downloaded to the edge server

5.Level 4: training and inference in edge-cloud cooperation mode

6.Level 5: training and inference in in-edge mode, i.e., on edge servers

7.Level 6: DNN model training and inference in on-device mode

As the level of EI increases, the amount and path length of data offloading decreases. As a result, data offloading transmission latency decreases, data privacy increases, and WAN bandwidth cost is reduced. However, this is achieved at the cost of increased computational latency and energy consumption.

This conflict indicates that there is no “best level” in general; rather, the “best level” of IE depends on the application and must be determined by jointly considering multiple criteria such as latency, energy efficiency, privacy, and WAN bandwidth cost.

Distributed DNN training architectures at the edge can be divided into three modes: centralized, decentralized and hybrid.

In the centralized mode, the DNN model is trained in the cloud datacenter. The data for training surveillance. Once the data is received, the datacenter cnto are generated and collected from distributed end devices, such as cell phones, cars, and diloud cameras performs DNN training using this data. Therefore, the system based on the centralized architecture can be identified in cloud intelligence level 0, level 1, level 2 or level 3 depending on the type of inference used.

In the decentralized mode, each edge server/local device locally trains its own DNN model with local data, preserving private information locally. In order to obtain the global DNN model, improvements to the local training must be shared; therefore, nodes in the network will communicate with each other to exchange updates to the local model. This mode corresponds to EI level 5.

The last mode is the hybrid mode, in which the centralized and decentralized modes are combined. In this case, edge servers can train the DNN model either through decentralized updates with each other or through centralized training with the cloud datacenter. This mode corresponds to EI levels 4 and 5.

As I have already anticipated throughout the article, the characteristic parameters to be monitored in the implementation of an EI model are bandwidth and energy efficiency, latency, communication cost, reliability, and security. To remind us of these, the acronym BLERP (Bandwith, Latency, Economics, Reliability, Privacy) was coined by Jeff Bier, founder of EDGE AI and Vision Alliance.

We analyze in the following how they affect the training phase.

Complex model training is data-intensive because raw or intermediate data must be transferred between nodes. Intuitively, this communication overhead increases the energy, bandwidth consumption and latency of training. Thus, the communication overhead is affected by the size of the original input data, the transmission mode, and the available bandwidth.

Thus, energy efficiency can also be considered as a bandwidth-related parameter (amount of data that needs to be transmitted). When training the DNN-type model in a decentralized way, for example, both the computation and communication processes consume a lot of energy. However, for most end devices, energy is limited (battery power). As a result, it is necessary for model training to be energy efficient.

Latency is probably one of the most important indicators of distributed training because it directly affects the time when the trained model is available for use. The latency of the distributed training process typically consists of computation latency and communication latency. The computation latency is strictly dependent on the capacity of the edge nodes (edge datacenters and end nodes). Communication latency may vary from the size of the raw or intermediate data transmitted and the bandwidth of the network connection.

Device connectivity costs a lot in economic terms. The more bandwidth required, the more the cost increases. Doing the training on the edge (on edge datacenters or where possible on local devices) saves a lot of money. In any case, the economic impact should not be overlooked because it cannot always be solved by introducing edge-computing.

Data privacy should also not be neglected. Limiting connectivity to the edge preserves the privacy of the data, since it should not be transmitted through the communication network with the cloud. For example, in the case of video analytics, rather than streaming video and audio to a remote server, the “intelligence” encapsulated in an EI-ready camera can be used to process learning algorithms with DNN.

Let us now look at the types of architectures that can be used for inference.

(a) Edge-based mode: Device A is in edge-based mode, which means that the device receives input data and sends it to the edge server. When inference is performed by the edge server, the prediction results are returned to the device. In this inference mode, since the model is on the edge server, it is easy to deploy the application on different mobile platforms. However, the main disadvantage is that the inference performance depends on the network bandwidth between the device and the edge server.

(b) Device-based mode: Device B is in device-based mode. The mobile device obtains the model from the edge server and performs model inference locally. During the inference process, the mobile device does not communicate with the edge server. Therefore, the inference is reliable, but it requires a large amount of resources such as CPU, GPU and RAM on the mobile device. The performance depends on the local device itself.

(c) Edge-Device Mode: The C device is in edge-device mode. In edge-device mode, the device first partitions the model into multiple parts based on the environmental factors of the connected system, such as network bandwidth, device resources, and edge server workload. Then, the device executes the model up to a specific layer and sends the intermediate data to the edge server. The edge server runs the remaining layers and sends the prediction results to the device. Compared with the edge-based and device-based modes, the edge-device mode is more reliable and flexible.

d) Edge-Cloud Mode: Device D is in edge-cloud mode. It is similar to the edge-device mode and is suitable for the case where the device is severely limited in resources. In this mode, the device is responsible for collecting input data and the model is executed through edge-cloud synergy. The performance of this model is highly dependent on the quality of the network connection.

It should be emphasized that the four edge-centric inference modes mentioned above can be adopted simultaneously in a system to perform complex AI pattern inference tasks (e.g., cloud-edge-device hierarchy), efficiently using heterogeneous resources among a multitude of end-devices, edge nodes and clouds.

The same parameters considered for training processes must be considered for inference, especially for EI layers that affect edge devices more than edge servers.

Local devices often capture more data than the available transmission bandwidth. Imagine a smart sensor monitoring the vibration of an industrial machine by capturing audio signals on which to perform inference. The data collected can be millions in a very short time. What might happen if all of them were not processed or the sensor lost crucial data just before breaking down? What could happen if, given the very large number of samples collected, the partial loss related to the energy efficiency of the device occurred? [2]

Regarding latency, for example, for some real-time intelligent mobile applications (e.g., telemedicine, AR/VR mobile games, and intelligent robots), the requirements are very stringent, such as 100 ms latency. Energy also has tight constraints for inference because of the battery power of the devices and the energy required for computation.

With the exception of the device-based mode, the communication overhead greatly affects the inference performance of the other modes

Memory usage in performing inference especially on mobile devices is also a parameter to be carefully evaluated. Indeed, on the one hand, a DNN model comes with millions of parameters, which can be very demanding on the hardware resources of mobile devices. On the other hand, unlike high-performance discrete GPUs in data centers, there is no dedicated high-bandwidth memory for GPUs on mobile devices. In addition, CPUs and mobile GPUs typically compete for shared and scarce memory bandwidth. For edge-side DNN inference optimization, memory footprint is a non-negligible indicator. The memory footprint is mainly affected by the size of the original DNN model and the way the tremendous DNN parameters are loaded.

With this article I have tried to highlight the special features of Edge AI and how it represents the new paradigm for development. It thus opens the way for a wide range of new applications in which the extreme responsiveness of the computational system is required.

In summary, Edge AI is revolutionizing the hitherto known world by making realtime data central to economic and technological development, ushering in a new era, that of decentralized artificial intelligence.It should be emphasized that the four edge-centric inference modes mentioned above can be adopted simultaneously in a system to perform complex AI pattern inference tasks (e.g., cloud-edge-device hierarchy), efficiently using heterogeneous resources among a multitude of end-devices, edge nodes and clouds.

The same parameters considered for training processes must be considered for inference, especially for EI layers that affect edge devices more than edge servers.

Local devices often capture more data than the available transmission bandwidth. Imagine a smart sensor monitoring the vibration of an industrial machine by capturing audio signals on which to perform inference. The data collected can be millions in a very short time. What might happen if all of them were not processed or the sensor lost crucial data just before breaking down? What could happen if, given the very large number of samples collected, the partial loss related to the energy efficiency of the device occurred? [2]

Regarding latency, for example, for some real-time intelligent mobile applications (e.g., telemedicine, AR/VR mobile games, and intelligent robots), the requirements are very stringent, such as 100 ms latency. Energy also has tight constraints for inference because of the battery power of the devices and the energy required for computation.

With the exception of the device-based mode, the communication overhead greatly affects the inference performance of the other modes

Memory usage in performing inference especially on mobile devices is also a parameter to be carefully evaluated. Indeed, on the one hand, a DNN model comes with millions of parameters, which can be very demanding on the hardware resources of mobile devices. On the other hand, unlike high-performance discrete GPUs in data centers, there is no dedicated high-bandwidth memory for GPUs on mobile devices. In addition, CPUs and mobile GPUs typically compete for shared and scarce memory bandwidth. For edge-side DNN inference optimization, memory footprint is a non-negligible indicator. The memory footprint is mainly affected by the size of the original DNN model and the way the tremendous DNN parameters are loaded.

With this article I have tried to highlight the special features of Edge AI and how it represents the new paradigm for development. It thus opens the way for a wide range of new applications in which the extreme responsiveness of the computational system is required.

In summary, Edge AI is revolutionizing the hitherto known world by making realtime data central to economic and technological development, ushering in a new era, that of decentralized artificial intelligence.

[1] cfr. Daniel Situnayake, Jenny Plunkett “AI at the Edge” O’Reilly e Zhou e altri: “Edge Intelligence: Paving the Last Mile of Artificial Intelligence With Edge Computing”, Proceedings of IEEE

[2] https://afassio.github.io/2022/07/20/M&AM-july-2022_English_version.html